Trade Openness and Entrepreneurship in Africa

Eric Boccaccio and Jhaelle Payne

3/30/21

Abstract

This study examines the correlation

between Trade Openness and Entrepreneurship in 5 African nations: Angola,

Egypt, Madagascar, Morocco, and Sudan. While previous research has shown a

positive correlation between these factors in other regions (Bayar et al. 2018),

this is the first study that exclusively focuses on low to medium-low income African countries. Due to limitations in data

availability, the design of this study is cross-sectional, meaning that it only

examines data for one time point, 2018.

Using a linear regression model, we found

that—holding

poverty, average years of education, and law and order constant—a 10%

increase in trade openness will lead to a 5.75% increase in

entrepreneurship on average. Although we found a positive correlation, there

is not enough data available to reject the null hypothesis that no correlation

exists between these two factors in Africa.

Future study requires more abundant and frequent regional

entrepreneurship data, as more data points are needed to judge whether or not the correlation found in this study is

significant.

Keywords: Entrepreneurship, Africa,

Trade, Trade Openness

Introduction

This study analyzes the correlation

between trade openness and entrepreneurship in 5 African nations: Angola,

Egypt, Madagascar, Morocco, and Sudan.

In recent years, there has been an increase in

cooperative trade deals between African and non-African countries. Often, these

deals are made by African leaders with the intent to stimulate economic growth.

To citizens, the commonly cited justification for trade openness is that a

better economy creates a more upwardly mobile populace.

To test this theory, we’ve

decided to focus on one method of attaining upward mobility, entrepreneurship.

We aim to examine how trade openness correlates with entrepreneurship using

data from 5 African nations. We control for education, strength of

governance, and poverty levels.

Literature Review

The Relationship

Between Trade Openness and Entrepreneurship

This study analyzes the correlation between trade openness and

entrepreneurship in 5 African nations. While past scholarship has shown

these two factors to be positively correlated, the African region has not been

a focus of previous work. Bayar et al. (2018) studied 15

countries worldwide from 2001-2015 and found that “banking

sector and capital market development, FDI inflows, and trade openness affect

the total early-stage entrepreneurial activity positively.”

Notably, of the 15

countries that Bayar et al. considered, only one (South Africa) was located in Africa. The study also was

exclusively limited to upper-middle and high income countries,

whereas all 5 countries in this study were classified as either

lower-middle or low income at the time of data collection.

Importance of

Studying Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship has long been thought to be a key method of

attaining upward socioeconomic mobility. While there are few studies examining

the relationship between entrepreneurship and socioeconomic development in

Africa (Nafukho and Helen Muyia 2010), studies in Latin America have shown

that “entrepreneurship is a channel of intergenerational

mobility,” with most of this mobility being upward (Castellani and Lora

2014).

Entrepreneurship has

also been shown to drive overall economic growth in Africa. Adusei (2016) compared results from 12 African countries

and found that “entrepreneurship positively explains the variations in the

growth of the study countries.” He goes on to contend

that “entrepreneurship in developing economies including Africa, even if

replicative, is instrumental to economic growth.”

Why focus on

Africa?

Africa is an important region to study in this context due to its

recent rapid increase in entrepreneurship levels (Singh and Belwal 2008). This increase is especially

intriguing given Africa’s colonial history. By the end of the

European imperial era, the region had been stripped

of much of its culture, resources, and governmental structures

(Halkias, et al. 2011).

After

the imperial powers exited the region, Africans were forced to

rebuild their societies with very little resources. Some African countries

have thrived, while others have yet to fully recover. Therefore, it is

important to understand what factors contribute to African

economic and socioeconomic growth. In this study, we examine the

relationship between two known predictors of economic growth: how

trade openness correlates with entrepreneurship.

Trade Openness

In the past, trade openness has been shown to correlate with a

variety of factors. Le Goff and Singh (2013) studied the relationship between

trade openness and poverty in a panel of 30 African countries from 1981 to

2010. After controlling for factors such as education and strength of

governance, they found that “trade openness tends to reduce poverty in

[African] countries where financial sectors are deep, education levels high and

governance strong.” This study and Le Goff and Singh’s work use

similar experimental methodology and control factors.

To test the impact of trade openness on economic growth in

Africa, Brueckner and Lederman (2015) studied 41

African nations and found that “trade openness has a significant positive

effect on economic growth.” Controls included GDP growth of trading

partners, civil conflict, and even amount of rainfall.

Methodology

This

study is designed to determine whether a correlation exists between trade

openness and entrepreneurship levels in 5 African nations: Angola, Egypt,

Madagascar, Morocco, and Sudan. The study controls for poverty, education, and

strength of governance.

Data

Table 1 — Variable Definition and

Sources

|

Variables |

Description |

Data Sources |

|

Trade Openness Independent

Variable |

Sum

of imports and exports as a share of GPD |

World

Bank Financial Statistics |

|

Entrepreneurship Dependent

Variable |

Proportion

of the population actively engaged in starting or running a new

business |

Global

Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) |

|

Poverty |

Percentage

of the population living below the $1.90/day poverty line |

Euromonitor

International Passport: Economies and Consumers |

|

Law and Order (Strength of Governance) |

Strength

and impartiality of the legal system, and popular observance of the law. Values

range from 0 to 6, with a higher figure indicating a

higher quality and more enforced legal system |

International

Country Risk Guide (ICRG) |

|

Education |

Population-weighted average

years of formal education |

Global

Health Data Exchange (GHDE) |

Data Sources:

All

data was collected from established datasets. Data on trade openness was

collected from the World Bank. Entrepreneurship data comes from the Global

Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM). Data on education was collected from

the Global Health Data Exchange (GHDE). To measure quality of governance,

we used a law-and-order indicator from the International Country Risk Guide

(ICRG). Poverty rates were sourced from Euromonitor International’s Economies

and Consumers dataset. Raw data can be found in the appendix of

this report.

Measurement Procedures:

Trade Openness (independent

variable/input):

In

economics, there are two accepted ways to measure trade openness. The first

method is policy based; a measure of the openness of a particular country’s

trade policy. The second method is outcome-based, which boils down to the

amount of trade taking place across a given country’s borders (Spilimbergo et al. 1999). For

the purpose of this study, we found an outcome-based measurement to

be the most practical option. Not only is outcome data easier to obtain, it also provides a more complete view of each country’s

total level of trade in the market.

The most common outcome-based measurement of trade openness

is the sum of imports and exports divided by a country’s GDP, and this is the

method used here. Data is provided by the World Bank. Because the latest

available entrepreneurship data for the selected countries is from 2018, trade

openness data will also be taken from that year.

Entrepreneurship (dependent variable/output):

The

Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) measures entrepreneurship levels through

use of survey data.

The

GEM bases results on two surveys, the Adult Population Survey (APS) and the

National Expert Survey (NES). The APS has a sample size of at least 2,000

working age adults in each country and asks about “entrepreneurial

activities, attitudes, motivations and ambitions” (Bosma et

al. 2020). The NES samples responses from at least 36 national experts in

each country who provide insight on government policy, infrastructure,

availability of entrepreneurial education, and more.

Based

on the survey responses, a Total Early-Stage Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA)

index is created. Each country is assigned a TEA value for a given year. The

TEA is defined as “the proportion of the working-age adult population actively

engaged in starting or running a new business.” In this case, any business

younger than 42 months is counted as new.

Because the 2019 GEM report includes fewer African

countries, data is sourced from the 2018 report.

Control

Variables:

To attempt to isolate the relationship between our two main

variables, we have chosen to control for 3 additional factors.

Poverty is measured using the poverty

headcount index, which is the percentage of a country’s population that lives

below a set poverty line. The current International Poverty Line is $1.90 USD

per day accounting for differences in purchasing power between

currencies.

Educational attainment is

measured by average years of formal education among the

country’s populace and is population weighted.

Strength of governance takes into account the strength and impartiality of the

legal system, and popular observance of the law. The ICRG uses

quantitative analysis, forecasting, and data series to measure political risk

by country.

These 5 data sources pay particular attention to

their methods for obtaining data because developing countries lack statistical

infrastructure, which can lead to inaccurate results.

Statistical Method

To estimate the relationship between entrepreneurship level

and trade openness, all other factors in the compiled dataset were controlled.

To achieve this, linear regression was used to measure the exact effect a 10%

increase in trade openness has on entrepreneurship levels, given all other

variables are held constant. Then, a scatter plot displayed the residual values

compared to the fitted values, to understand the accuracy of the model.

Results

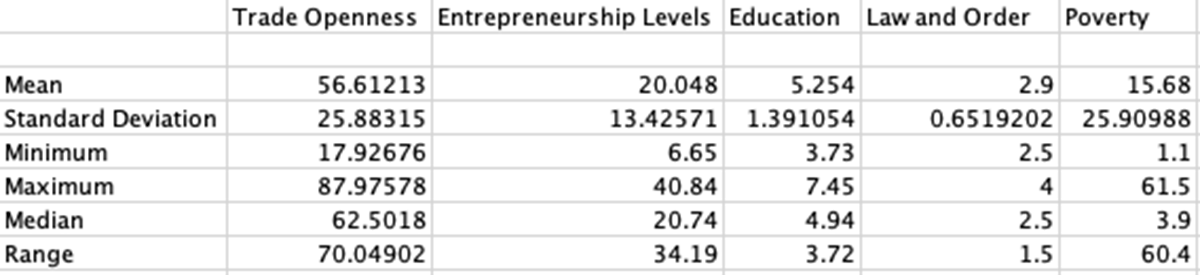

Figure 1

Summary Statistics of

Numerical Variables

Figure 1 displays the mean, standard

deviation, minimum, maximum, median and range of the numerical variables. The

high standard deviation in Trade Openness, Entrepreneurship Levels, and Poverty

indicates that the data points are more spread out. Also, in Trade Openness,

Entrepreneurship, and Poverty, the range values are particularly high which

highlights the vast political, economic, and social differences between the

observed countries.

Figure 2

The Correlation

Between Entrepreneurship Levels and Trade Openness

Figure 2 displays a

visual representation of the correlation between Trade Openness and

Entrepreneurship by Country. Given that there is not a linear trend between the

two variables, when performing linear regression, a logarithmic transformation

will have to be used on the data values.

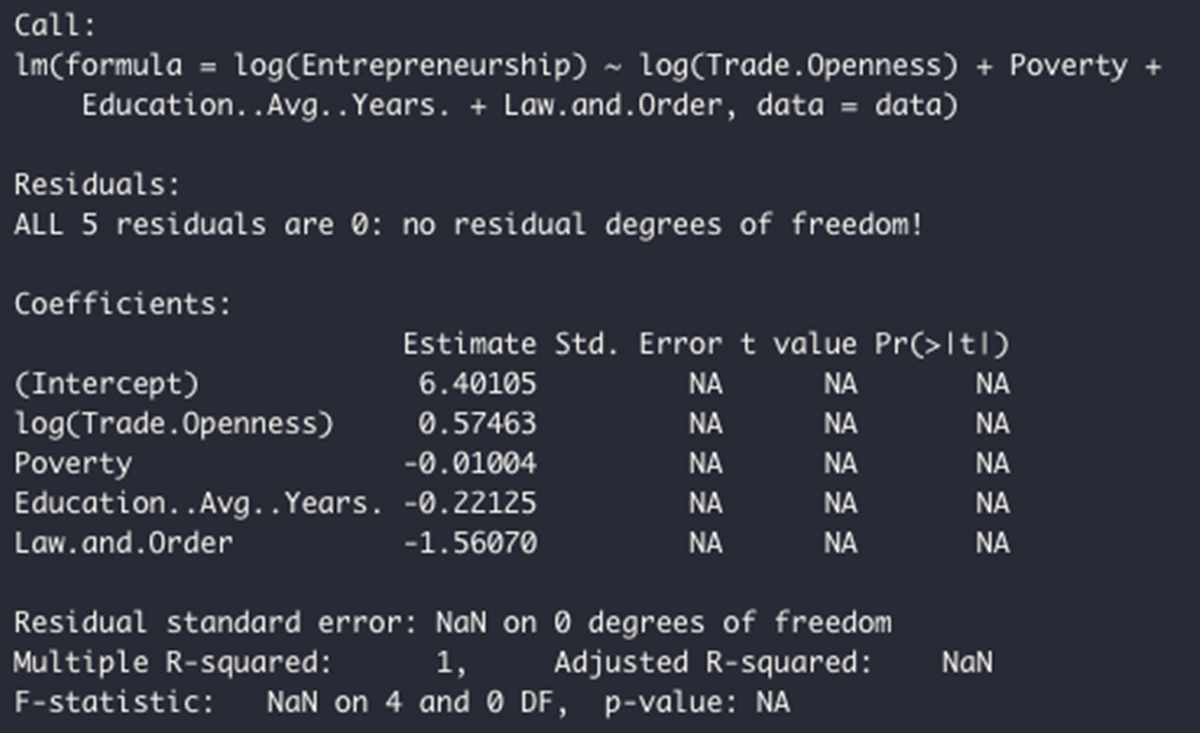

Figure 3

The Predicted Percent

Change in Entrepreneurship Level for A 10% Increase in Each Variable, Holding

the Other Variables Constant

In Figure 3, our final

model is as follows:

log(Entrepreneurship) =

.575*log(Trade Openness) + -.01*Poverty + -.22*Average Years of Education +

-1.56*Law and Order.

Holding poverty, average years of education, and law and order

constant, a 10% increase in trade openness will lead to a 5.75% increase in

entrepreneurship on average. This exhibits a positive correlation between trade

openness and entrepreneurship levels within Angola, Egypt, Madagascar, Morocco,

and Sudan. Logarithmic transformation was used because the data values are

nonlinear. A logarithmic transformation can transform a skewed dataset into a

normalized one, where the shape of the values become closer to a normally

shaped bell curve. Only the log of the values shift, not the raw data. This

transformation also allows the model to produce the smallest error possible

when predicting values while preventing overfitting.

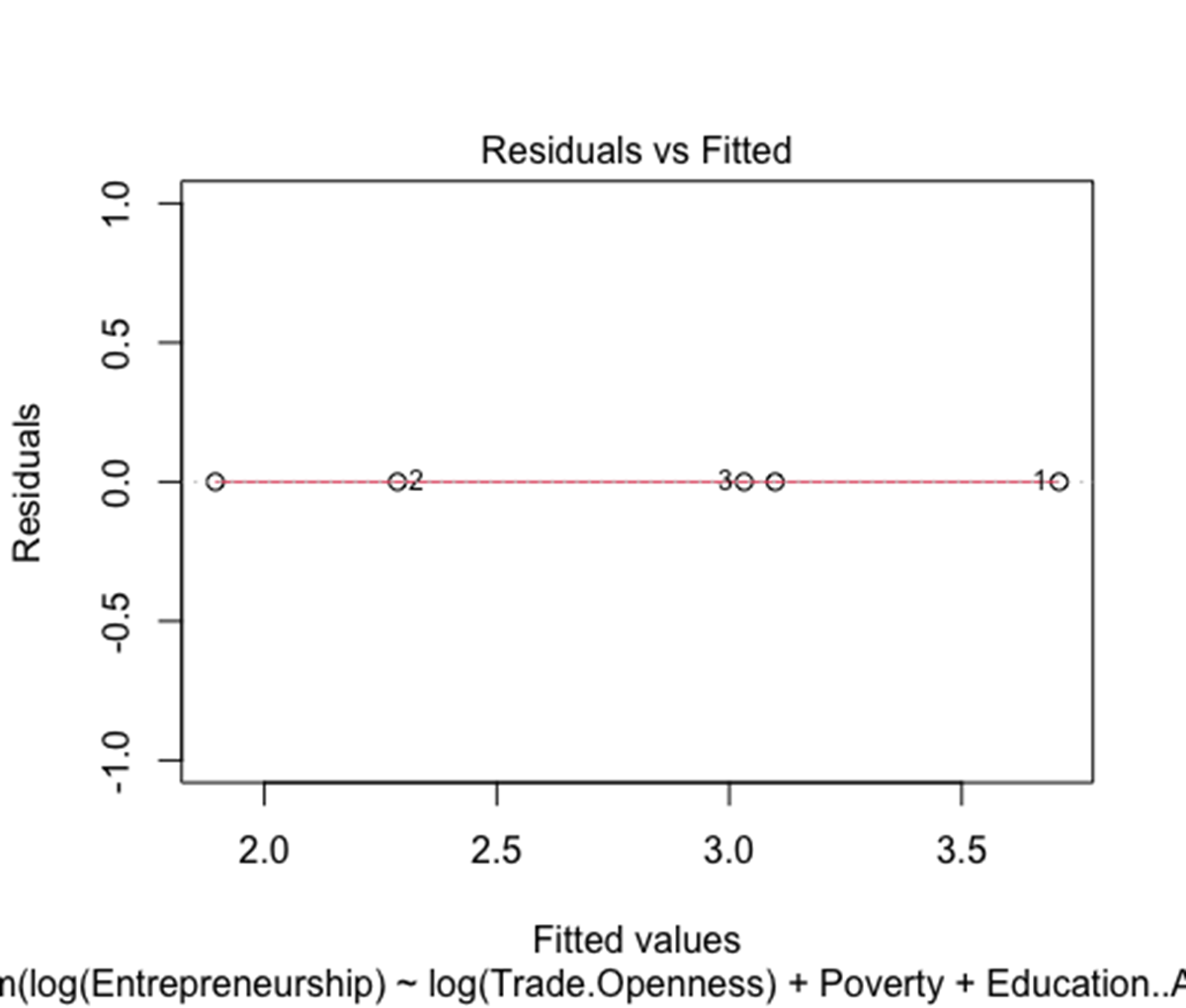

Figure 4

The Residual Values

Compared to the Fitted Values

In Figure 4, the

scatter plot demonstrates the accuracy of the predicted values. In which, the

model was able to predict the values with high accuracy. This is shown through

the lack of outliers and its residual value of 0, meaning there is not a

numerical difference between the fitted and predictor values.

Discussion and Limitations

Variables

Variables were

chosen based on Le Goff and Singh’s (2013) work on the correlation between

trade openness and poverty. Le Goff and Singh found that “trade openness tends

to reduce poverty in [African] countries where financial sectors are deep,

education levels high and governance strong.” Therefore, this study controls

for poverty levels, education levels, and strength of

governance (law/order). Because our instrument only allows for three

control factors, we were unable to include financial sector

strength as a control.

Data

There are a few

limitations stemming from the data used in this study, mostly having

to do with age and availability.

Total

Early-stage Entrepreneurial Activity

To create a valid cross-section, we needed to make sure that datapoints

for each country were taken from the same year. While the Global

Entrepreneurship Monitor does contain entrepreneurial

activity data for 20 African countries, not every country is

measured annually. In the past 5 years, the year containing the

highest concentration of data from African countries in a single timepoint

was 2018; with data from Angola, Egypt, Madagascar, Morocco, and

Sudan. Therefore, our cross-section was limited to a maximum of 5

countries.

The lack of

consistent annual African entrepreneurship data is also the

reason why a time-based model, such as the one used by Bayar et al.

(2018), was unfeasible in this study.

Average Years of

Education

Although every other factor considered in this study uses

data taken in 2018, the Global Health Data Exchange only

has relevant education data available up to

2015. Therefore, the education data used in our model is

about three years older than the rest of the

data. While we cannot ensure that this data remains accurate in

2018, we can test the degree to which education

data varies in the time leading up to

2015. In the three-year period from 2012-2015, mean

years of education for our 5 countries deviates by about 0.13

years on average.

If this

trend continued for the following three years, we can assume that the mean years of education

in 2018 should be roughly similar to 2015 plus or minus a few

months. This relatively small degree of uncertainty is unlikely to have

changed our results significantly.

Percent

of Population Living Below International Poverty Line ($1.90 a Day)

The poverty data

used in this study is 2018 estimates from Euromonitor

International’s Passport. Euromonitor estimates this data using

previous poverty estimates released by the World Bank. The

methodology that Euromonitor uses to calculate these yearly

estimates, however, is unclear. This being said,

Euromonitor International is a trusted, well established

market research corporation.

Model/Research

Design

This study is also limited in the sense that it provides a cross

section of variables at only one time point, 2018. Because we were unable to

model these variables over time, it is possible that the correlation we found

between entrepreneurship and trade openness in 2018 doesn’t

exist at other time points. This being said, we estimate the

probability of 2018 being an outlier to be small, especially given

that Bayar et al. (2018) found a similar relationship between these two

variables worldwide in a study spanning 14 years. Given the differences between

the countries studied here and the ones included in the work of Bayar et al.,

however, it is still worth noting the limitations of having used a

cross-sectional method.

Also,

through performing a backwards stepwise regression, we found that our Law and Order variable would have been a better indicator of

Entrepreneurship Level. A backwards stepwise regression starts with a model

containing every variable, then at each step it removes a variable to find a

regression model with the least number of variables needed to explain the data.

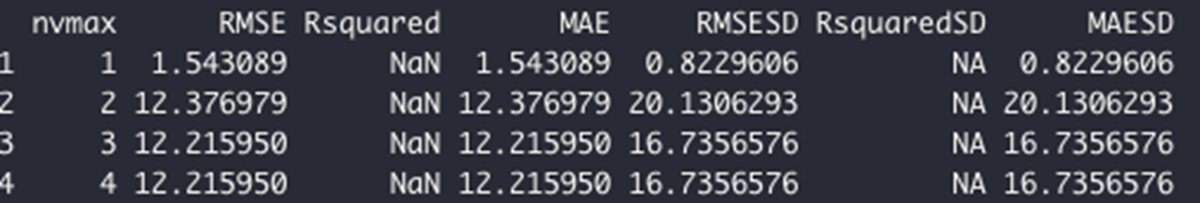

Figure 5

Training

the Model

Figure

5 demonstrates the backwards stepwise regression testing a certain number of

variables at a time in the model. The column “nvmax”

displays that number of variables. The Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Mean

Absolute Error (MAE) demonstrates that one variable in the model will best

explain the data. Specifically, the lower RMSE and MAE value is, the lower the

bias. This will ensure that our model is as accurate as possible because lower

bias is an indication of higher accuracy.

Figure 6

The

Best Set of Variables for the Model

![]()

After

training on the data, figure 6 demonstrates which variables will best explain

the data. In which only Law and Order was selected by placing an asterisk under

the variable.

Significance,

Future Study, Policy Recommendations

Because of our limited number of data points, it’s impossible to reject the null hypothesis that

trade openness has no effect on

entrepreneurship in Africa. Therefore, the initial results found

here need to be validated by further study. This being

said, our results do show trade openness and

entrepreneurship to be positively correlated. This is the case even

when accounting for our control factors of education, poverty, and

law/order.

In the future, yearly entrepreneurial activity

estimates will be needed for more countries in Africa. This way, a

longitudinal study that includes more datapoints can

be conducted. A study with more complete data would be able to determine

with more certainty if a significant correlation exists between trade openness

and entrepreneurial activity.

Also,

given our findings that Law and Order best explains

entrepreneurial activity in this dataset, it will certainly be worth studying

the relationship between these two factors in future as well.

Until more complete data is collected and

analyzed, no political or policy recommendations can be made to the leaders of

Africa regarding trade openness and entrepreneurship. This

being said, trade openness and entrepreneurship are both

known indicators of economic growth as discussed in detail in

the literature review portion of this report. Therefore, it would likely

be beneficial for African leaders to continue the push toward a more

globalized economic structure.

Appendix — Merged Data

|

Country |

Trade Openness (%) |

Entrepreneurship (%) |

Poverty (%) |

Education (Avg. Years) |

Law and Order (0-6) |

|

Angola |

66.37801194 |

40.84 |

10.7 |

4.94 |

2.5 |

|

Egypt |

48.27827106 |

9.84 |

1.2 |

7.45 |

3 |

|

Madagascar |

62.50180122 |

20.74 |

61.5 |

5.54 |

2.5 |

|

Morocco |

87.97578268 |

6.65 |

1.1 |

3.73 |

4 |

|

Sudan |

17.92676158 |

22.17 |

3.9 |

4.61 |

2.5 |

References

Adusei, M. (2016), Does Entrepreneurship Promote Economic Growth

in Africa?. African Development Review, 28: 201-214. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8268.12190

Bayar,

Y., Gavriletea, M., & Ucar,

Z. (2018). Financial Sector Development, Openness, and Entrepreneurship: Panel

Regression Analysis. Sustainability, 10(10), 3493. MDPI

AG. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/su10103493

Bosma et al. (2020). Global Entrepreneurship

Monitor 2019/2020 Global Report. Global Entrepreneurship Research Association.

Brueckner, M. and Lederman, D. (2015), Trade Openness and Economic Growth:

Panel Data Evidence from Sub‐Saharan Africa. Economica,

82: 1302-1323. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecca.12160

Castellani, Francesca,

& Lora, Eduardo. (2014). Is Entrepreneurship a Channel

of Social Mobility in Latin America?. Latin American Journal

of Economics, 51(2), 179-194. https://dx.doi.org/10.7764/LAJE.51.2.179

Halkias, D., Nwajiuba, C., Harkiolakis, N. and Caracatsanis,

S.M. (2011), "Challenges facing women entrepreneurs in

Nigeria", Management Research Review, Vol. 34 No. 2, pp.

221-235. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409171111102821

Le

Goff, M. & Singh, R.J. (2013). Does Trade Reduce Poverty? A View

from Africa. Policy Research Working Paper 6327, The

World Bank, Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Unit. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-6327

Nafukho,

F.M. and Helen

Muyia, M.A. (2010), "Entrepreneurship and socioeconomic

development in Africa: a reality or myth?", Journal of

European Industrial Training, Vol. 34 No. 2, pp. 96-109. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090591011023961

Singh,

G. and Belwal, R. (2008), "Entrepreneurship

and SMEs in Ethiopia: Evaluating the role, prospects and problems faced by

women in this emergent sector", Gender in Management, Vol. 23 No. 2, pp.

120-136.

Spilimbergo, A., Londoño J.L.,

Székely, M. (1999), Income distribution,

factor endowments, and trade openness, Journal of Development Economics, Volume

59, Issue 1, pp. 77-101, ISSN 0304-3878. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3878(99)00006-1.

Appendices

Jhaelle and Eric split the final report. Jhaelle wrote the Results,

Methods and Keywords section. Eric wrote the Abstract, Introduction, Literature

Review, Discussion and Limitations, and Significance, Future Study,

Policy Recommendations sections. Jhaelle also helped with a portion of the

Literature Review and Discussion and Limitations sections. Jhaelle created

Figures 1-6, and Eric created Table 1 and the Appendix. Eric sourced and

compiled the data, and Jhaelle created the linear regression model.